- Home

- Klaus Modick

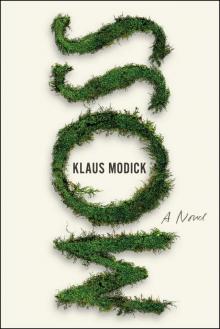

Moss

Moss Read online

Moss

Moss

Klaus Modick

TRANSLATED BY

David Herman

First published in the United States in 2020

by Bellevue Literary Press, New York

For information, contact:

Bellevue Literary Press

www.blpress.org

Moss was originally published in German in 1984

as Moos by Haffmans Verlag.

Text © 1984 by Klaus Modick

© Verlag Kiepenheuer & Witsch GmbH & Co. KG,

Cologne, Germany

Translation © 2020 by David Herman

This is a work of fiction. Characters, organizations, events, and places (even those that are actual) are either products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Modick, Klaus, author. | Herman, David, 1962- translator.

Title: Moss / by Klaus Modick ; translated by David Herman.

Other titles: Moos. English

Description: First edition. | New York, NY : Bellevue Literary Press, 2020. | Moss was originally published in German in 1984 as Moos by Haffmans Verlag. | Translated from the German

Identifiers: LCCN 2019031919 (print) | LCCN 2019031920 (ebook) | ISBN 9781942658726 (trade paperback) | ISBN 9781942658733 (ebook)

Classification: LCC PT2673.O24 M613 2020 (print) | LCC PT2673.O24 (ebook) | DDC 833/.92--dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019031919

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019031920

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or any information storage and retrieval system now known or to be invented, without permission in writing from the publisher, except by a reviewer who wishes to quote brief passages in connection with a print, online, or broadcast review.

Bellevue Literary Press would like to thank all its generous donors—individuals and foundations—for their support.

This publication is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature.

The translation of this work was supported by a grant from the Goethe-Institut.

Book design and composition by Mulberry Tree Press, Inc.

Bellevue Literary Press is committed to ecological stewardship in our book production practices, working to reduce our impact on the natural environment.

This book is printed on acid-free paper.

Manufactured in the United States of America

First Edition

1 3 5 7 9 8 6 4 2

paperback ISBN: 978-1-942658-72-6

ebook ISBN: 978-1-942658-73-3

For M. J. G.

Content

Preliminary Note by the Editor

Moss

Translator’s Note

Moss

PRELIMINARY NOTE BY THE EDITOR

THE DEATH OF Professor Lukas Ohlburg, who died in the spring of 1981, at the age of seventy-three, has resonated far beyond the realm in which he did his botanical research, giving rise to expressions of sympathy and grief in the wider sphere of scientific life. Numerous obituaries and appreciations in newpapers and journals—and not just scientific journals—have noted that because of Ohlburg’s death the natural sciences in general, as well as botany in particular, have sustained a considerable loss. Apart from his field-specific investigations, of which his two major studies of tropical and subtropical forms of vegetation have long been counted among the classics of modern botany, Ohlburg’s essays critiquing the terminology of natural science have had a profound influence on theories about science itself. This work brought him not only significant acclaim but also strong criticism, given the nature of the subject and Ohlburg’s deliberately provocative way of treating it.

In the narrow circle of Ohlburg’s colleagues and friends, it was known that in the last years of his life he spoke frequently of wanting to combine these essays into a systematic work, which would bear the title Toward a Critique of Botanical Terminology and Nomenclature. It appeared, however, that he had never actually attacked this project; or at least no records or materials relating to it could be found in his unpublished scientific papers. I am honored that, in my capacity as Ohlburg’s long-standing assistant, it fell to me to undertake the task of sifting through these papers and editing them as necessary—a task that has since been completed (see Lukas Ohlburg, Botanical Reflections from the Unpublished Papers, Munich, 1982). That volume could not have been assembled without the kind cooperation of the brother of the deceased, Professor Franz B. Ohlburg, of Hanover, and after its publication I received a letter from him, at the end of 1982. I reproduce here, with his generous permission, an abridged version of Prof. Ohlburg’s letter, since it is of great importance for understanding the text published in what follows:

… You will receive a registered parcel by the same post; it contains a bundle of manuscript pages authored by my deceased brother. As you know, he left, along with the scientific texts that you edited, an even greater number of personal notes. These were, basically, diaries, which in accordance with his last will and testament I have destroyed unread. But as for the manuscript in question, for a long time I was uncertain whether it should be viewed as personal in nature or, rather, as a text suitable for publication. After repeated readings—made all the more difficult by the manuscript’s having been written, in part, in shorthand—I have come to the conclusion that my brother did think of these materials as part of his planned Critique of Botanical Terminology and Nomenclature. Publishing these materials may thus correspond to my brother’s intentions, even though I have serious misgivings about taking that step. Before I express my concerns more fully, however, I need to communicate to you some of the details of my brother’s death, because these details throw a peculiar light on a manuscript that is itself quite strange.

My brother was, as officially announced, found dead in the country house in Ammerland that belonged to both of us. The date of his death, so far as that can be firmly established, was 3 May 1981; heart failure was given as the cause of death. My brother had secluded himself in this house starting in September 1980, in order to work on his project there. Although he was not in the best of health because of his heart disease, he insisted on taking care of himself, categorically refusing any help in the house. You probably know better than I how stubborn he could be, especially when he was working.

I visited him there at Christmas that year. He struck me as being happy, relaxed, and unusually upbeat. The only change I noticed was that he had let his beard grow out. His mental state appeared to be clear—though, looking back, I would now freely admit that some of his comments should have made me suspicious. On 11 May 1981, I received a phone call from the village police station, informing me that my brother had died. I drove there the same day. The farmer living in the neighborhood, Hennting, had alerted the police after my brother had failed to make his customary trip to the farm to pick up his mail and purchase any necessities.

When I first arrived in the house, my brother’s corpse had already been taken to the village of Wiefelstede. The village doctor, who had issued the death certificate, gave me the following account: Despite the rainy weather of the preceding days, the doors and windows of the house had been left open. My brother was lying in front of his writing table, his body already slightly decomposed; the state of his body was attributable to the high moisture level in the house. Curiously, mossy growths were found on his face, particularly around his mouth, nose, and eyes, as well as in his beard. For understandable reasons, his corpse had to be put in a coffin immediately. But even so, with

the exception of his overgrown beard, my brother’s body did not strike me as being unkempt; nor did he appear to be undernourished. Similarly, the house was, as I made sure, in a clean and orderly condition, though with an odd exception: Patches and cushions of moss were scattered everywhere; the writing desk and likewise the floor were littered with them. Even the bed pillow was strewn with various mosses; some of these had withered, but others, because of the dampness in the house, were still green. This state of affairs explained the “mossification” of my brother’s mortal remains. On his writing table lay, amid the mosses, the aforementioned manuscript as well as an uncapped fountain pen. Hence my brother seemed literally to have died at his desk.

Once you have read it, you will understand why I hesitated so long before releasing this text. Even as a lay botanist, I venture to say that that these pages are likely to be of little interest vis-à-vis botanical research. Indeed, I doubt that my brother wrote this text in full possession of his mental faculties. If, as his brother, I find the confusion of his thought and language regrettable, as a psychologist I find it alarming. Indeed, although my brother continually refers to the project as a critique of terminology, the text as a whole strikes me as being the psychogram of his advancing senility. Given that my brother’s scientific reputation has never been subject to the slightest doubt, however, I will not block the publication of this text. Nevertheless, I do wish to express, in emphatic terms, my reservations concerning the views expressed herein. The title page, along with a few other passages, indicate that my brother wanted to publish the text. I believe that I am honoring his wishes in leaving this manuscript with you….

So much for the statement of Dr. Franz B. Ohlburg, whose reservations I share. The manuscript itself arrived in a brown cardboard folder, its deep grooves probably caused by exposure to moisture. The chronological sequence in which the individual pages were composed cannot be reconstructed. In any case, Ohlburg must have continued to work on the project until just before his death, albeit sporadically. Having been written on normal typewriter paper, the manuscript is divided, ostensibly at least, into two parts. The first third is written in shorthand with a pencil, that being Ohlburg’s preferred method of working. (He would later dictate his notes to his secretary.) But the last and greater part of the manuscript is written with a fountain pen in normal longhand, for which Ohlburg used green ink. The text itself goes into this matter. On the cardboard folder he used pencil to write the original title—Toward a Critique of Botanical Terminology and Nomenclature—in shorthand. Subsequently, though, this title was struck through with green ink and carefully rewritten as Moss. The prefatory quotation appears to have been copied down during this later phase, as well.

—K. M.

Hamburg, October 1983

Moss

And to the end I saw myself receding softly, like smoke, into the pores of the earth.

—Annette von Droste-Hülshoff,

“In the Moss”

I SHOULD HAVE RETURNED here earlier. Did I dread the memory? I wanted to be productive, to push something forward, drive it out of myself—something whose meaning, however, seems more and more elusive to me, the longer and more passively I accept, in myself, a mere being here. This acceptance is equivalent to a serenity, a kind of farewell to the empirical world, which I am losing interest in, becoming indifferent to. Such indifference takes the form of nothing being more important to me than anything else.

At this point I barely read the newspapers, and I do not keep a television or radio near me, nor pay them any mind. For days I have felt a kind of dizziness, a fading away. This is not the feeling brought on by the brutal blows of my heart attack, which forced me to become an emeritus professor a few years ago. It is, rather, a feeling of being pulled softly downward, although the direction in question cannot be correctly described as downward. In general, since my arrival here my thoughts, ideas, and sensations are of directionlessness and aimlessness, difficult to define, gleaming in a faint clarity wholly unknown to me up to this point, a vague, indeterminate everywhere. The perception of this deconcentration, inimical to thought, is intense—indeed, overly clear. Although I did not come here to let myself go, I do not resist.

When we were children, there could be no talk of such instability, such groundlessness, because Father, even while on holiday here in the country, placed by far the greatest value on discipline—and by that he meant composure. Was that why, later on, I was never at ease in the house? It was only Franz and his family who spent summers here; I always traveled farther. Even now I find traces of my nephew, Franz’s son, and his family in the house: children’s drawings on the walls, a turntable with a collection of rock-music records, and textbooks on sociology and economics, most of them written from a neo-Marxian perspective.

Sometimes I enjoy browsing through these textbooks. I amuse myself by considering how they derive ridiculous problems from the most banal platitudes of a crude, primitive epistemology. They use a discourse that no longer even grasps its own content, because its concepts have choked out all intuition, because the abstract is too seldom brought into relation with the concrete; by way of compensation, the discourse inclines toward verbal tricks of an almost artistic sort. But through this very romanticization of scientific discourse, something like knowledge occasionally shines through.

Analytic and dialectical thinking has probably never led to understanding, to real knowledge, to truth in a comprehensive, almost metaphysical sense. As is well known, Hegel in his Logic poses the remarkably nonsensical question of whether it is not an “infinitely higher achievement to capture the form of the syllogism than to describe a species of parrot or a veronica plant”; and how much higher is such an achievement as compared to describing a humble moss! To be sure, contemporary science seeks to wash itself clean of such ignorantly arrogant rationalism; yet it washes and washes and still is not able to remove the stain of such nature-despising cynicism from its pale skin. If I only knew how to describe what a lower animal, a tree, or even a moss really is, I could care less about the 2,048 possible forms of logical syllogism that Leibniz enumerated in his combinatory analysis. He must have been very bored, that old couch potato….

As for the botanical terminology used as a naming system for the natural phenomena in which, for example, this house lies embedded: In the best case it says only what grows here, albeit in a soulless and uncomprehending way. Never can it say how, and never with full certainty could it say why. And perhaps it is better that way.

When it comes to the magnificent old pine tree whose branches beat against my upper windows, I can name it “correctly” and conceptually disassemble it right down to its molecular structure. But I have no way of describing the language with which the tree, in knocking against the window, speaks to me.

UNDOUBTEDLY, BOTANY, like any science, requires a simple, clear, internationally accepted nomenclatural system. On the one hand, the terms of this nomenclature are used to mark off the various ranks within a taxonomy of systematically arranged groups or units; on the other hand, they function as scientific names that designate particular taxa of plant groups. But in my view it is undeniable that this very nomenclature, instead of deepening our knowledge of the objects and phenomena that it serves to classify, contributes to an always increasing estrangement of the researching subject from what he or she is investigating. The term, the name, does not simply provide a means for classifying a phenomenon or object; what is more, in being identified with or reduced to any such classification, the object or phenomenon is short-circuited, regarded as understood, as known.

Now to some degree, this way of proceeding is necessary in order for any general scientific consensus to be achieved; but it may be, in the final analysis, the goal of all science. What we find in contemporary botanical literature and research is a theory that yields classifications without real knowledge. I myself participated in this kind of research all my life, to the best of my ability and in good conscience—and with a not inconsid

erable amount of success. I feel compelled, however, to think otherwise, to speak otherwise, before it is too late for me.

But how? In attempting to develop a plausible critique of botanical terminology, of scientific discourse in general, and ultimately of scientific thinking and method per se, I am faced with a dilemma. Is there a language that can capture and transmit real knowledge? (It remains to be clarified what this knowledge is—if it can, in fact, be “clarified.”) Such a language must surely be one that renounces intersubjectively binding, one-dimensional cataloging and categorization; a language—and here is the paradox—that defines insofar as it gives expression to the undefinable. It must be a language that does justice to singularity and particularity, placing more trust in intuitions than fixed concepts.

As I write this down, I realize that in advancing such a construal of formal, academic science, I am getting lost, going astray. Among the circle of my highly esteemed colleagues, no one will take me seriously. Here I allow myself a way of thinking, a form of expression, that before I always warned my pupils, research students, and colleagues against. Yet it seems to me as though I were being allowed to use just this sort of language. But by whom?

A PICTURE-BOOK INDIAN SUMMER brings warm temperatures once again. At night one already gets an indistinct sense of fall, but by day it is still as warm as high summer. I take advantage of the weather by going swimming regularly. Toward evening, as the day gradually cools down, there is an exact instant when the water and air temperatures equalize. That is the best moment. No further transitions can be sensed; the specific qualities of the different states of matter melt into one another.

My physician has gently warned me to cut back on my swimming somewhat, but the half hour that I need to swim across the lake and back causes me no difficulty whatsoever. The slight tiredness that, without inducing sleepiness, comes over me more and more frequently, settling into my muscles and bones, dissipates when I swim. The weightlessness that water provides loosens my muscles, eases my joints, and also sometimes drifts through my thoughts like a rising mist. For many people, walking relaxes the mind; for me, it has always been swimming. The flow of my thoughts synchronizes with the movements of my body. One reaches far out and then, as it were, returns back to oneself again. Taking swift breast-strokes, I have sometimes planned out presentations, sometimes whole lectures.

Moss

Moss